By Prafulla Mohanti - 01 Jan, 2013

Brahma, Vishnu, Maheswar

The teacher took my right hand and with a Thick Clay Chalk helped me to draw three perfect circles on the mud floor. It was my initiation into the world of art and learning. I was three years old and was taken to the village chatshali by my grand mother who could not read or write but determined to educate her grandson. I remember my first day at the chatshali. I carried a brass plate on which was arranged some rice, a coin, a dhoti for the teacher, some flowers with sandalwood paste and a coconut. I bowed down to pay respect to the teacher who blessed me by gently stroking my outstretched palm with his cave. Then he helped me to draw three perfect circles while chanting Brahma, Vishnu, Maheswar. It was my first drawing lesson and I practised the circles for several months chanting the divine names over and over again. There were three other children going through the same ceremony and as we drend the circles and chanted Brahma, Vishnu, Mahesh. The village reverberated with the holy sound.

As I look back I find how profound the system was. It was like a performance and installation art. The oriya script is round and practising. The circles helped me to develop a good hand writing. As I went on practising the circles and chanting Brahma, Vishnu, Maheswar it became a mantra and evoked a sense of meditation in me. It is only now after many years of drawing the circles I realize that at the age of three I was defining and creating the images of the divine inside an infinite space of Shunya without form and colour. While drawing the circles and chanting the sacred names I was inviting the divine energies to come and live in them.

As I looked around the village I saw the presence of the divine energy everywhere, in people and in the landscape. The circle became the Bindu, the red vermillion spot on my mother’s forehead which glowed like the rising sun.

The name of my village is Nanpur, situated on the right bank of the river Birupa, in the Jaipur district or Orissa. It is surrounded by paddyfields, mango groves and palm trees swaying in the wind like dancers. In the distance there is a range of hills containing ancient buddhist monuments of Udaygiri and Ratnagiri. The river gives Nanpur its identity and plays an important role in its life. In my childhood when the river overflowed during the monsoon the whole area became a lake with villages standing like islands, I enjoyed visiting my friends on rafts made from banana trunks. In the summer the riverbed dried up and provided me with a bed of clean sand on which I played with my friends making patterns with my feet. The whole village was my playground and I played everywhere. I watched the colours of the ricefields change from vivid green to golden yellow, the sweet scented flowers which opened out at night, the multicoloured birds who filled the village air with their songs, the stars, the planets and the brilliant sunsets and sunrises. It was magic and I felt at one with nature. My realization of the relationship between Purusha and Prakriti began. The villagers live in close contact with nature, worship the mother earth and celebrate the first rain fall after the not summer months with a ritual which is compared with her fertility.

Art was a part of life. The villagers decorated the walls and floors of their mud houses with ricepaste for religious and social ceremonies. My mother was a good painter and I followed her instinctively. I became so good that I was invited by other villagers to decorate their homes. Their appreciation gave me encouragement. The lotus was the main symbol and I saw the circle becoming a Lotus and I enjoyed the process of improvisation. At harvest festival it was used with stylised foot prints to welcome Laxmi, the goddess of wealth into the house.

The villagers saw their gods and goddess both as figures and abstract forms. While some villagers saw Durga with ten arms, riding a lion, others saw her as an earthen pot filled with water. A red Sari with garlands of hibiscus flowers are arranged around the pot. The priest draws a diagram with coloured powder, lights an oil lamp and a wood fire is lit on which ghee is poured; each item in the worship is carefully selected giving importance to its design and beauty. As the flames leap and the smell of incense fills the air, the space comes to life and the pot becomes the living symbol of the goddess. The village women create symbolic images of Mangala, the mother goddess by digging a rectangular mound on the village path with a round form in the centre. It is worked with turmeric water, decorated with vermillion paste and worshipped to protect the children. Laxmi the goddess of wealth is created with a basket filled with fresh paddy and decorated with an orange Sari and garlands of marigold flowers. I drew the figures of Jagannath, an incarnation of Vishnu around the altar containing the tulsi plant during the holy months of Kartik. Orissa village culture is influenced by Jagannath culture of universal love. The rice offered to the deity is dried and sold to pilgrims who carry it to their homes. The dried rice is called ‘nirmalya’ which has the power to purify the soul and build ever lasting friendships between people of different caste and religion. From my childhood I have considered ‘Jagannath’ as my friend and protector and drawn and painted him in different forms and colours, always oval with his all seeing round eyes.

I saw my mother worship Vishnu in the form of an oval stone called Shalagram which she placed horizontally on a small round copper plate. Every morning after having her bath she worshiped it, anointed it with sandalwood paste. At the Shiva temple I saw the priest worship the image of Shiva in the form of an oval stone placed exect on a concave stone platform.

Malhia Buddha which protects the village sits under an ancient varuna tree at one corner of the village. It is in the shape of a Shiva Lingam covered in layers of vermillion paste by the villagers who are not aware of its phallic symbolism. I watched villagers select oval stones, Smear them with vermillion paste, decorate them with red hibiscus flowers and transform it from ordinary to extraordinary and sacred the Mangala, the mother goddess.

There are many centres of Shakti worship in Orissa. For one month beginning from the end of the spring to the beginning of the summer - 13 March to 13 April - the attendants to the goddess dress as the goddess and go around villages carrying the symbolic images of the goddess on their heads and spreading the gospel of the goddess. They perform yogic dances, walk on sticks with acrobatic postures. As I watched them I was totally mesmerised by their unique spiritual presence. The red is the colour of the goddess and they carried vermillion paste with them and blessed the villagers by putting vermillion Bindus on their foreheads.

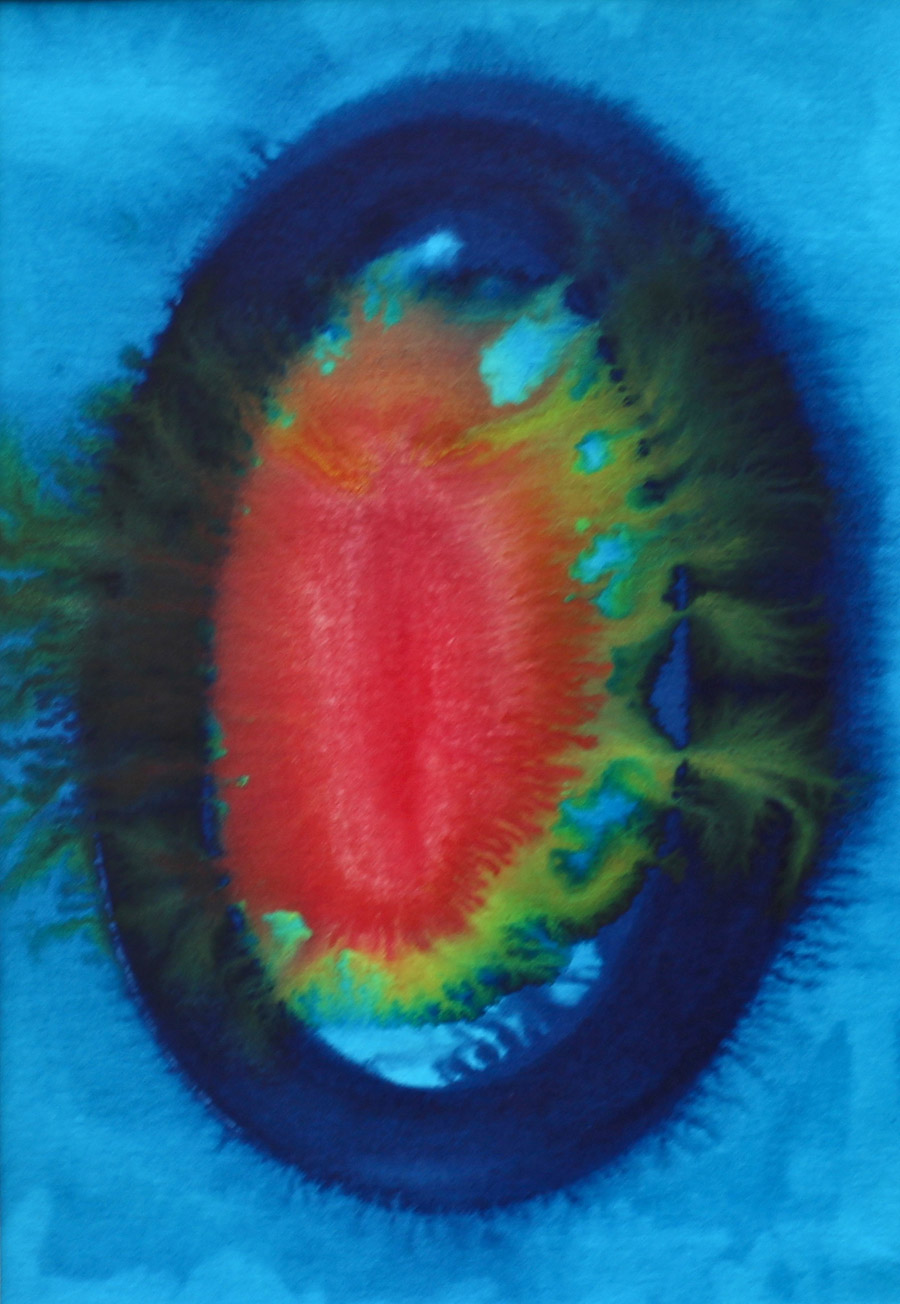

When I went to study town planning in the industrial city of leeds in England. I rented a bed sitting room in a large vicrorian house. The walls of the room were covered with grey wall paper. Wherever I cooked I saw only grey. The city was grey with grey chimneys belching out grey smoke. I missed the colours of my village and I could not relate myself either to the city or to my grey room. So I took large pieces of drawing paper and painted them with symbols of the Lotus and Jagannath in bright colours and put them on the walls of the room. Immediately the character of the room changed and provided me with a space in which I felt spiritually comfortable. Every evening after my classes I came to my room and painted. As I went painting , a process of self realization began. The circles became ovals, circles and ovals and Bindus came together - the village symbols became personnel symbols wihc became universal symbols of life, love and energy.

I went on playing with colours taking water as a medium which has a life of its own. Controlling it provided me with a challenge and I went on experimenting and expressing myself. The circles, the ovals and the Bindu kept appearing and reappearing .

The circle has been ingrained into my system and has moulded my thoughts. The Lotus of my childhood has undergone changes through abstraction, from a circle to a point, bindu. Absolute abstraction makes it disappear to shunya, from shunya life begins again and becomes everything, the total universe, the Brahmanda. Shunya is paripurna.

I understood the true meaning of pure abstraction when my mother died. She was dressed as a bride and taken to swargadwar, the door to heaven, the famous cremation ground on the shores of the bay of Bengal in the holy city of Puri of Jagannath. The priest chanted mantras and her body was placed on a bed of wooden logs with pieces of sandalwood and my elder brother lit the funeral pyre. I watched my mother’s beautiful body being engulfed by fire and turn into ashes and becoming shunya. It was a profound experience of spiritual and cosmic consciousness which made me realize that life is art and art is life, colour is life and life is colour. There is no life without colour. I express my emotions through colour and form which give me hope and a sense of awareness of shunya the total universe.